(Good but Weak, Strong but Bad, or Good and Strong)

Background

During the 1960s a popular and accessible model of psychotherapy, Transactional Analysis (TA), was developed by Eric Berne. Berne described his approach in his famous book, Games People Play.1 Everyone will recognize the players in TA’s examples of transactional “games.”2 TA continues to be a useful resource to understand how people’s relationship behaviors are adaptive or maladaptive. The model of unhealthy parent-child voices and healthy adult voices presented here comes from my clinical use of TA, which is based on an earlier TA adaptation by my genius psychiatric mentor, Boyd K. Lester, M.D. Of course, the current use of this model is for informational purposes only and is not intended to replace the need for formal psychotherapy. The parent-child and adult voices language used here is significantly different than Eric Berne’s and Thomas Harris’s descriptions of ego-states in the Transactional Analysis model. The term “childish,” centrally located in this model, was not used at all by Berne.

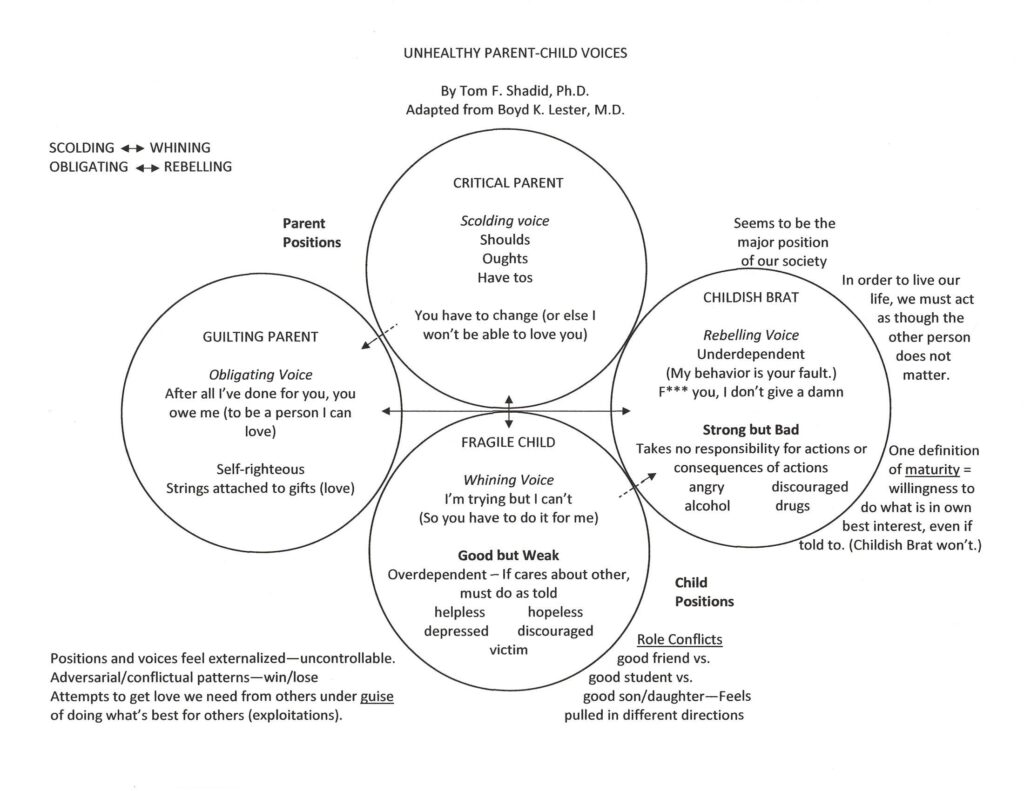

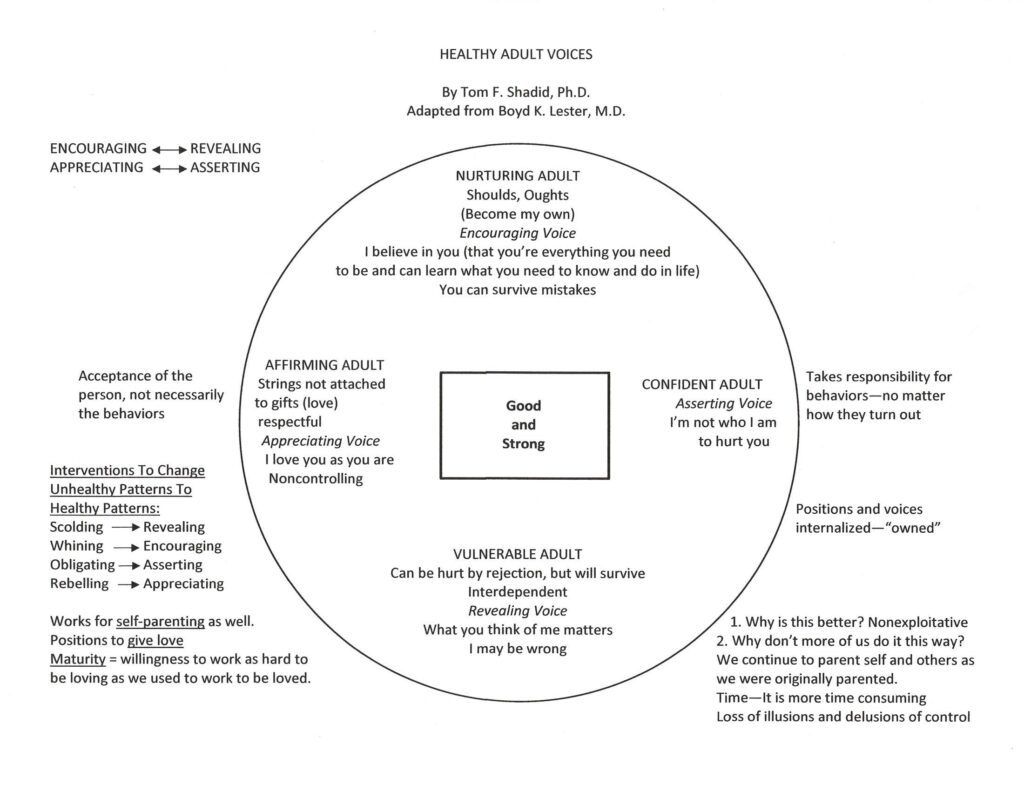

When I first presented this model to parents and teachers in the 1990s, it was not related to the quadrune mind model. However, I believe this educational model fits very well with the quadrune mind model of consciousness as described in the Study Guide and our other QM blogs. The two figures below, “Unhealthy Parent-Child Voices” and “Healthy Adult Voices,” illustrate the points that I will make about relationships in this essay.

Introduction

The way we learned to relate to our parents as we grow up influences the way we relate to people in general. It also strongly impacts how we communicate as adults with our children, employees, or other people who may be in a subordinate position to us. Unfortunately, our own parents may not have been all that adult when they raised us. They may have been stuck in a childish mentality themselves because of the immaturity (lower levels of consciousness in the quadrune mind model) of their own parents. These unhealthy patterns have a way of being handed down from generation to generation. Through repetition over time, these “games” have become ritualized by individuals, families, and society. In the quadrune mind model, ritualized behavior is a reptilian-minded trait3 and this mind is highly resistant to change. In this essay I will elaborate on how our unhealthy and healthy voices relate to the quadrune mind model of consciousness.

Figure 1. “Unhealthy Parent-Child Voices” shows two pairs of unhealthy parent-child voices. The critical parent’s scolding voice interconnects with the fragile child’s whining voice, and the obligating voice of the guilting parent interconnects with the childish brat’s rebelling voice. The unhealthy parent positions are included as “childish” voices because of their inappropriately immature level of consciousness. These unhealthy voice patterns preserve the adversarial relationship we originally had with our parents, or parental figures. Because these conflicting voices remain “dissociated” from each other, we continually feel psychologically and emotionally conflicted within ourselves and with other people. Furthermore, these voices seem “external” to us and uncontrollable by us, because we have never really “owned” them—rather they “own” us. They became our voices before we could consciously choose them. I will discuss how each voice is expressed in our lives and in society in harmful ways.

Figure 2. “Healthy Adult Voices” illustrates the healthy adult version of the “childish” parent-child relationship voices. I will describe how a healthy adult voice in response to the immature childish voices in others can help them become more effective adult communicators. Any relationship becomes more productive and satisfying when we use an adult voice, whether we’re speaking with authority figures, peers, or subordinates. In this integrated healthy version of parent-child voices, we have made the voices ours; we “own” an integrated personalized voice. With intentional practice this new healthier way of relating will be experienced emotionally and mentally by us as natural and normal.

Unhealthy Childish Voices

Critical Parent’s Scolding Voice. The critical parent scolds the child as unlovable when the child’s behavior causes the parent to feel “bad.” The parent scolds in the hope of quickly stopping the child’s behavior that is causing the parent distress. The child gets the implicit message that they4 “should” be different than they are; otherwise, they may be abandoned by the parent. The parent may feel “bad” when a crying child is sick and the parent cannot afford medical care for the child, or the parent is exhausted from work and financial stressors and doesn’t have the energy to play when the child wants to play. The scolding voice is used when the parent does not know a better way to meet a child’s legitimate needs—and fears that the child’s needs cannot be met.

Fragile Child’s Whining Voice. The scolding voice elicits the whining voice of the overly dependent child. The critical parent’s message, “You must change!” elicits the fragile child’s response, “But I can’t—you have to do it for me!” The fragile child has learned that loving (needing) someone means doing what the other person says must be done in order to preserve the relationship. This belief persists into adulthood for many people. The position of the fragile child is a state of being “good but weak.” Historically, girls were raised to remain “good but weak,” fragile children throughout their lives. The whining voice is used by the fragile child to elicit the scolding voice, which tells the child that the “parent” (authority figure) is accepting responsibility for the child’s behavior.

Guilting Parent’s Obligating Voice. The obligating voice is used to control the behavior of a child who is rebellious, rather than whiny. The critical parent’s “You must change!” said to a childish brat receives a response of, “F… you!” The childish brat is fighting against judgmental criticism that the child perceives as unfair. The purpose of the obligating voice is to make the child feel guilty for having a strong, independent voice or opinion. The guilting parent says, “After all I’ve done for you, this is the way you repay me?” The message is that the “love” the parent has shown the child has strings attached. Love was not freely given, but was “transactional” in the business sense: quid pro quo. This is an example of applying the so-called “business model,” which often stifles Human consciousness, to human relationships.5 The guilting parent’s obligating voice is antagonizing to the childish brat, which justifies further guilting by the parent when the child rebels. This dynamic can be seen when law enforcement agents provoke peaceful social protestors to defend themselves, resulting in “justified” escalated violence against the “rebelling” voice of the protestors, as seen through the childish parents’ “guilting” eyes of the agents.

Childish Brat’s Rebelling Voice. The rebelling childish brat blames the guilting parent as the cause of all of the problems in the relationship. The childish brat takes no responsibility for the consequences of their behavior, especially the pain it causes the guilting parent: “I don’t give a damn what you think!” (Or how you feel.) One definition of maturity is, “Doing what is in your own best interest, even if someone tells you to.” The immature childish brat is not capable of this type of maturity. For example, the childish brat would go hungry rather than eat their favorite meal if someone told them to eat it. The childish brat will use alcohol/drugs, sex, violence, reckless driving, abusive authority, or vulgar language to prove that nobody can tell them what to do or not do. In order to feel strong, the childish brat has to be “bad.” Historically, boys have been raised to adopt the childish brat position, a voice that many people in American society seem to prefer today (we see more childish brats in power than fragile children and we tend to be more critical of whining voices than childish rebelling ones). The childish brat’s irresponsible rebelling voice seems justified to them by the injustices (which may be real) done to them.

How to Respond with Healthy Adult Voices to Unhealthy Childish Voices

Nurturing Adult’s Encouraging Voice to the Fragile Child’s Whining Voice. Whether it is our actual children, an employee, or anyone else who is in a subordinate position to us, we may hear complaints that we are expecting more from the person than they are able to give. Instead of scolding a whiny person pleading helplessness, the healthy adult can respond with an encouraging voice. The nurturing adult can express such things as, “I understand that this work is hard. I believe you can do hard things, like when you took care of the shop all day by yourself.” Or “You may not know how to interview for a job, but I believe you can learn how to do it.” Perhaps, most importantly, the nurturing adult can say with conviction, “You can survive your mistakes.”

Vulnerable Adult’s Revealing Voice to the Critical Parent’s Scolding Voice. When we are reprimanded by someone with authority over us, such as a parental figure or boss, a healthier response than the fragile child’s whining voice or the childish brat’s rebelling voice is the vulnerable adult’s revealing voice. The vulnerable adult acknowledges that what the other person thinks is important. Although the vulnerable adult can feel hurt when rejected by an important person in their life, the adult will survive and can live well. The vulnerable adult is not overly dependent on others, but recognizes that we are all interdependent and what we do affects each other.

Affirming Adult’s Appreciating Voice to the Childish Brat’s Rebelling Voice. When someone is “bratty” to us, we can be respectful to the feelings of the childish brat without becoming self-righteously defensive about it. We can listen with a real intent to understand how the person sees things that are leading them to act “hatefully,” such as the belief that they have been treated unfairly in some way. This awareness can help the adult clear up a misunderstanding or model a more mature way of handling frustration to the child (or childish, immature “grown up”). The affirming adult is willing to discuss what the conflict is about, even at the risk of learning that the childish brat has a legitimate complaint, which may influence the adult to change their own thinking.

Confident Adult’s Asserting Voice to the Guilting Parent’s Obligating Voice. The confident adult in us has the same assertive voice as the childish brat does, except the confident adult takes responsibility for their actions. The other person may react with a childish guilting voice, but the confident adult is able to say, “Even though you are upset, I am not doing what I’m doing to hurt you. I am doing what I’m doing because I believe it’s the best thing to do.” There is no “power struggle,” because the confident adult is not trying to control the other person in order to get “permission” to do what they believe is right. At the same time, if the action taken actually ends up being a bad idea, the confident adult does not become a “bad” person, because they acted in good faith and take responsibility for remedying any negative consequences of their actions and learning from their mistake. The confident adult can be strong, and wrong, without being bad.

Conclusion

To change from inappropriate childish to healthy adult speaking voices requires some intentional practice for most of us. Old programmed childish speech inevitably negatively impacts our lives without our awareness. Any skill we acquire to help us move out of our childish (reptilian and old mammalian) mindsets into a more adult Human consciousness enables us to become more spiritually aware and more fully engage with life. When we use our adult voice, we help others develop a more adult voice themselves. As fellow adults we gain a deeper appreciation of the people with whom we live and together contribute to a healthier global society.

Resources

Berne, E. (1964). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. New York: Grove Press.

Harris, T. A. (1969). I’m OK—You’re OK: A practical guide to transactional analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

- Berne, E. (1964). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. New York: Grove Press. “The somber picture presented in Parts I and II of this book, in which human life is mainly a process of filling in time until the arrival of death, or Santa Claus, with very little choice, if any, of what kind of business one is going to transact during the long wait, is commonplace but not the final answer. For certain fortunate people there is something which transcends all classifications of behavior, and that is awareness; something which rises above the programing of the past, and that is spontaneity; and something more rewarding than games, and that is intimacy. But all three of these may be frightening and even perilous to the unprepared” [page 184].

- A contributor to TA theory and practice was Dr. Wilder Penfield, a neurosurgeon from McGill University in Montreal. Transactional analysis was popularized by Berne’s student Thomas A. Harris. “The ‘games’ that people played were like worn-out loops of tape we inherited from childhood, yet continued to let roll. Though limiting and destructive, they were also a sort of comfort, absolving us of the need to really confront unresolved psychological issues…. Harris used Berne’s work as a basis for his own, but instead of analyzing the games we play, focused on the internal voices that speak to us all the time in the form of archetypal characters: the Parent, the Adult and the Child (the PAC framework). All of us have Parent, Adult or Child ‘data’ guiding our thoughts and decisions, and Harris believed that transactional analysis would free up the Adult, the reasoning voice [new mammalian mind]. The Adult in us prevents a hijack by unthinking obedience (Child) [old mammalian mind], or ingrained habit or prejudice (Parent) [reptilian mind], leaving us a vestige of free will.” [The reasoning mind in the quadrune mind model is categorized as an adolescent new mammalian mind {see pages 5-7, 9-10 of the Study Guide}. The quadrune mind model conceptualized the “adult” as possessing a spiritually actualized Human mind that goes beyond reason as the highest good to wisdom as the highest good. As many people do, Harris probably assumed that “reason” is the “highest” mental capacity of human brains].

- See the “reptilian” mind on page 9 of the Study Guide

- Merriam-Webster. (2020). A note on the nonbinary ‘They’: It’s now in the dictionary. [Because of the problem in English regarding pronouns often denoting either gender or number inaccurately, it was the custom in the past to opt for accuracy in number (generally by using “he”) when referring to a single person of unknown gender over accuracy in gender. This is because grammarians used to think it was more important to be accurate on number rather than gender. This is an example of the abstractifying new mammalian mentality. It places the importance of an idea—numbers—over the impact this choice has on actual human beings, notably the women who are discounted when only “he” is used. In keeping with the quadrune mind model’s emphasis of the importance of caring for all people over abstract ideas, I have chosen in this essay to use the modern nonbinary “they” when referring to a single individual of an unknown gender.].

- See the Nothing personal, it’s just business section of our “QM and the Scary New Mammalian Mind of the 21st Century” blog.

2 replies on “QM, Unhealthy Childish Voices, and Healthy Adult Voices”

This is very helpful information about how we relate to those in our lives! And I love the graphs!

Thank you Kerri. The model seemed to have been useful when I used it with parents and teachers. I love the graphs, too.